The Comfortable Fiction

Most organizations describe their AI systems as automation.

Automation feels safe. It implies tools, efficiency, and retained control. The system accelerates work, but responsibility remains clearly human. When something goes wrong, accountability is obvious.

Yet many deployed AI systems no longer behave like automation. They recommend actions that are rarely challenged. They rank options that quietly become defaults. They generate outputs that downstream teams treat as decisions already made.

At that point, the system is no longer automating work.

It is delegating responsibility.

The problem is not that delegation is inherently wrong. The problem is that delegation has requirements, and most AI systems are not designed to meet them.

Why the Distinction Matters

Automation changes how work is performed. Delegation changes who is responsible for the outcome.

In classical organizational design, delegation is explicit. Authority is transferred alongside responsibility, escalation paths are defined, and failure is anticipated. Controls exist not because people are untrustworthy, but because responsibility must be traceable.

AI collapses this distinction by operating in the space between recommendation and action. A system can be formally framed as advisory while functioning as authoritative in practice.

This is the source of many applied AI failures: not model error, but responsibility ambiguity.

The Responsibility Gradient

Responsibility does not move all at once. It shifts gradually, often invisibly.

A decision-support system becomes trusted. Trust becomes reliance. Reliance becomes default behavior. Eventually, humans remain “in the loop” only as a formality.

At no point does anyone explicitly decide to delegate responsibility to the system. And yet, when outcomes occur, responsibility has already moved.

This gradient is rarely modeled, measured, or governed.

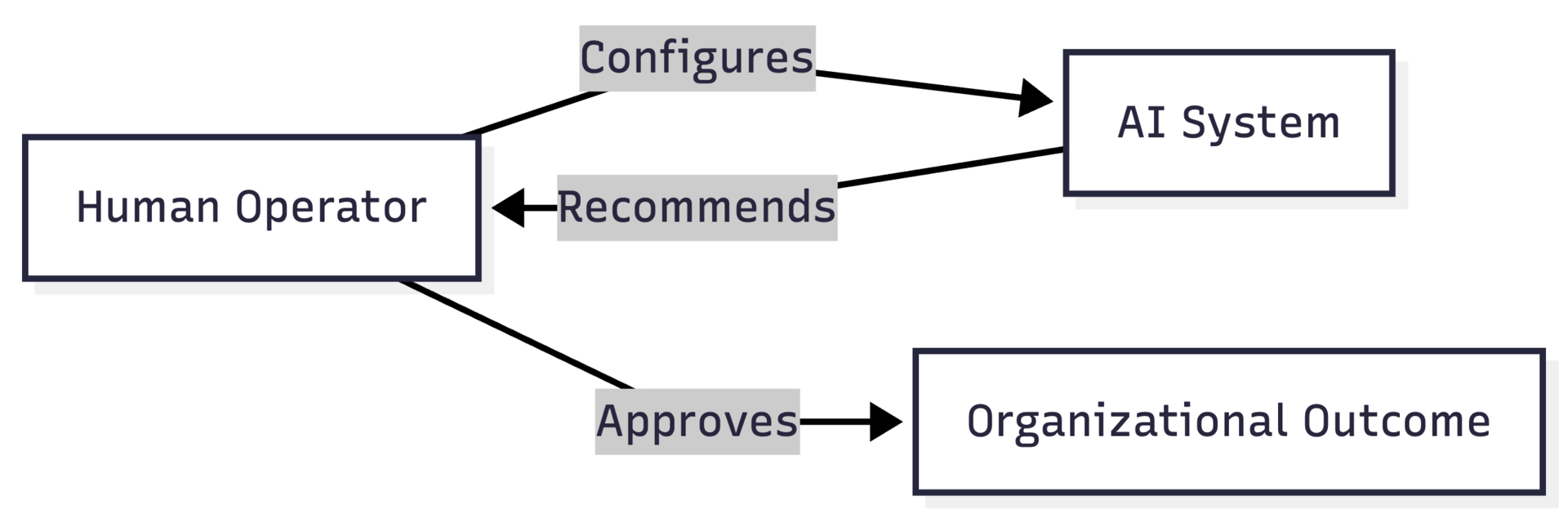

Figure: Nominal automation flow as described in policy.

When Policy and Reality Diverge

In practice, the flow often looks different.

Recommendations are accepted without review. Overrides exist but are socially discouraged. Metrics reward throughput, not deliberation. Over time, the organization adapts to the system rather than the other way around.

The system becomes the decision-maker in all but name.

At this point, the organization has crossed from automation into delegation – without acknowledging the transfer.

Figure 2: De facto delegation under the guise of automation.

The Cost of Ambiguity

When responsibility is unclear, failure becomes diffuse.

Teams argue about whether the system was “just a tool.” Leaders ask why humans didn’t intervene. Operators point to system outputs. Governance bodies search for policies that were never designed for this mode of operation.

The result is not accountability – it is paralysis.

This is why so many AI incidents feel unresolvable. The system did exactly what it was allowed to do. The organization never decided who was truly responsible.

The Missing Question

Most AI governance frameworks ask whether a system is accurate, fair, or compliant.

They rarely ask the more fundamental question:

Where does responsibility actually reside once this system is deployed?

Until that question is answered structurally – not rhetorically – organizations will continue to experience AI failures that feel mysterious but are entirely predictable.

What This Issue Will Establish

This issue argues for a clear boundary:

Automation retains human responsibility

Delegation transfers responsibility

AI systems must be designed and governed according to which side of that boundary they occupy, not which label is more comfortable.

The sections that follow examine how this boundary is crossed in practice, how it can be made explicit, and what structures are required when responsibility truly moves.

In the practitioner edition, this editorial includes:

Higher-resolution responsibility-flow diagrams

Explicit failure modes when responsibility is ambiguous

Design implications for architects deciding where authority should reside

These extensions do not change the argument. They make its consequences explicit.

IMPLEMENTATION BRIEF

When Decision Support Quietly Becomes Decision Making

Purpose

This brief examines a common applied AI failure mode: systems formally described as advisory that become authoritative in practice. The transition rarely involves a single design decision. It emerges from incentives, defaults, and operational pressure.

The Pattern

Decision-support systems are introduced to assist human judgment. They rank options, generate recommendations, or flag risks. Early usage is cautious. Operators compare system output with their own reasoning.

Over time, three things change:

The system becomes more accurate than any single operator.

Throughput expectations increase.

Overrides become socially and operationally expensive.

At this point, the system is still labeled “decision support,” but it is functionally deciding.

How the Shift Happens

The shift from support to authority is usually incremental.

Recommendations appear first in the interface.

Default actions are preselected.

Performance metrics reward acceptance over review.

None of these steps transfers responsibility explicitly. Together, they do.

Figure: Advisory framing with default-driven behavior.

Why “Human-in-the-Loop” Is Insufficient

Organizations often rely on human-in-the-loop controls to justify retained responsibility. The presence of a human approver is treated as evidence of oversight.

In practice, review becomes nominal when:

The cost of disagreement is high.

The system’s confidence is difficult to challenge.

Operators are evaluated on speed rather than judgment.

Responsibility appears to remain human, but decision authority has already moved.

Early Warning Signals

You are likely observing silent delegation if:

Overrides are rare and undocumented.

Teams defer to the system in post-incident reviews.

Operators describe the system as “usually right.”

These are not cultural problems. They are structural ones.

What This Enables and What It Breaks

Silent delegation can increase consistency and speed. It can also obscure accountability and suppress dissent.

When outcomes fail, organizations discover too late that no one was structurally responsible for the decision.

In the practitioner edition, this brief includes:

Alternative interface patterns that preserve genuine choice

Explicit decision thresholds and escalation points

Common implementation mistakes that accelerate silent delegation

These extensions do not prohibit delegation. They make it intentional.

IMPLEMENTATION BRIEF

Why “Human-in-the-Loop” Is an Incomplete Control

Purpose

This brief examines why human-in-the-loop controls often fail to provide real oversight in applied AI systems. The presence of a human reviewer is frequently mistaken for retained authority. In practice, review without power does not prevent responsibility transfer.

The Pattern

Human-in-the-loop is commonly implemented as a review step inserted after a system produces a recommendation or decision. The human is expected to approve, reject, or modify the output.

On paper, this appears to preserve accountability. In reality, the loop often functions as a confirmation ritual.

The system acts. The human ratifies.

Where the Control Breaks

Human-in-the-loop fails when the human role lacks one or more of the following:

The authority to materially alter outcomes

The time required for meaningful review

The information needed to challenge the system

Without all three, the loop exists procedurally but not structurally.

Figure: Nominal human-in-the-loop control.

Symbolic Oversight

In many organizations, review roles are introduced to satisfy governance expectations rather than to enable intervention.

Humans are placed in the loop after decisions are effectively irreversible, or when deviation is socially discouraged. Over time, reviewers learn that disagreement carries cost, while approval is invisible.

The loop remains. Authority does not.

The Illusion of Accountability

Post-incident analysis often reveals that no one felt empowered to challenge the system.

Leaders ask why the human did not intervene. Reviewers explain that the system was trusted, the output looked reasonable, or the window for action had passed.

Responsibility appears to exist everywhere and nowhere at once.

Early Warning Signals

Human-in-the-loop is likely symbolic if:

Review queues are consistently backlogged

Overrides require escalation or justification

Review metrics track volume, not disagreement

These signals indicate that the loop absorbs liability without providing control.

What This Enables and What It Obscures

Symbolic loops reduce organizational anxiety. They also mask where authority truly resides.

When failures occur, organizations discover that review steps did not function as safeguards. They functioned as insurance narratives.

In the practitioner edition, this brief includes:

A taxonomy of control surfaces beyond simple review

Criteria for meaningful human intervention

Failure paths created by late-stage oversight

These extensions reframe oversight as a design problem, not a staffing one.

SYSTEM COMPARISON

Automation Systems vs Delegation Systems

Purpose

This section makes a single structural claim: automation systems and delegation systems require fundamentally different controls, even when they appear operationally similar.

The comparison is visual and falsifiable. It is designed to surface where responsibility resides, how it moves, and where failures propagate.

Automation Systems

Automation systems augment human work while retaining human responsibility. The system accelerates execution, but authority remains clearly human.

Key properties:

Humans initiate and approve actions

The system optimizes within predefined bounds

Responsibility is legible before and after execution

Figure: Automation system with retained human responsibility.

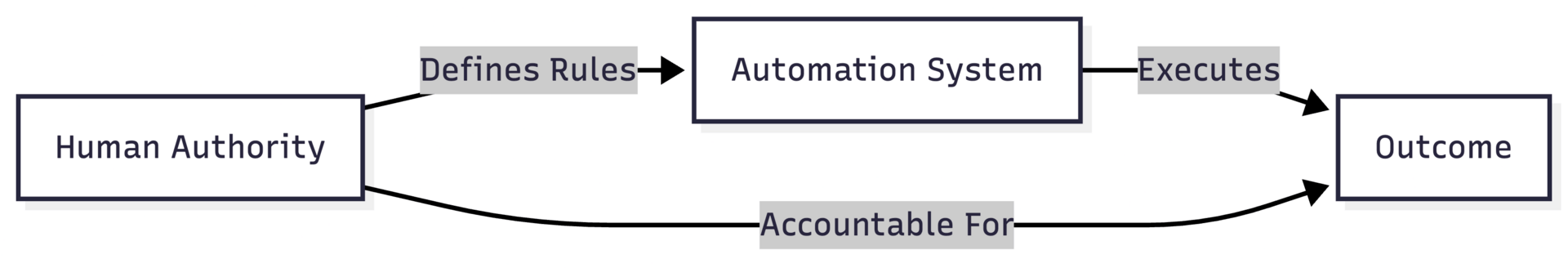

Delegation Systems

Delegation systems transfer decision authority to the system itself. Humans may configure, monitor, or intervene, but the system acts autonomously within its mandate.

Key properties:

The system selects and executes actions

Humans supervise rather than decide

Responsibility must be reassigned explicitly

Figure: Delegation system with transferred authority.

Why Confusion Occurs

Most applied AI systems sit uncomfortably between these models.

They are implemented as automation, described as assistance, and experienced as delegation. Controls designed for automation are applied to systems that behave as delegates.

This mismatch is the source of many AI governance failures.

Failure Propagation (High-Level)

When responsibility is unclear, failures propagate differently:

Errors are discovered late

Accountability becomes diffuse

Post-incident remediation focuses on models rather than structure

These patterns are predictable from the system design.

In the practitioner edition, this system comparison includes:

Higher-resolution versions of each diagram

Explicit failure propagation paths

Escalation, override, and kill-switch layers

Structural criteria for deciding automation vs delegation

These extensions show not just what the systems are, but how they break.

FIELD NOTES

Observation

Across recent applied AI deployments, a consistent pattern is emerging: teams believe they are piloting tools, while the organization experiences a system shift.

What begins as a contained experiment often crosses an invisible threshold. The system starts shaping workflows, influencing decisions, and setting expectations before anyone has agreed that delegation has occurred.

This transition is rarely explicit. It is inferred through use.

Pattern in the Field

Field interviews and post-incident reviews show the same sequence:

A pilot is introduced as an assistive system

Usage expands informally to adjacent decisions

Human review becomes advisory rather than determinative

Reversal becomes socially or operationally difficult

At no point is authority formally reassigned. The system simply becomes relied upon.

This is not negligence. It is structural drift.

Figure: Typical pilot-to-production drift pattern.

Why This Matters

Once reliance exceeds intent, controls lag reality.

Teams continue to apply automation-era safeguards to systems that now behave as delegates. Review processes assume reversibility. Monitoring assumes bounded impact. Accountability assumes a human decision that no longer exists.

When failures occur, the organization responds as if a tool misbehaved, rather than recognizing that authority had already shifted.

Signal to Watch

A practical indicator that a system has crossed the boundary:

Outputs are accepted during time pressure

Overrides require justification, acceptance does not

Teams refer to the system’s recommendation as the default

When these signals appear, the system is no longer experimental, regardless of its label.

Implication

The most dangerous phase in applied AI adoption is not large-scale rollout. It is the quiet middle period, where systems are widely used but still described as pilots.

This is where responsibility erodes without being reassigned.

In the practitioner edition, these field notes includes:

Structural mechanisms for containing pilot-to-production drift

Concrete intervention points that introduce deliberate friction

Audit questions for detecting unintended delegation early

Criteria for deciding when a pilot must be reclassified

RESEARCH & SIGNALS

Purpose

Research & Signals tracks developments that indicate structural shifts in how applied AI systems are being designed, governed, and deployed. The focus is not novelty, but implication.

The signals below are early indicators. None are decisive alone. Taken together, they suggest where applied AI practice is drifting.

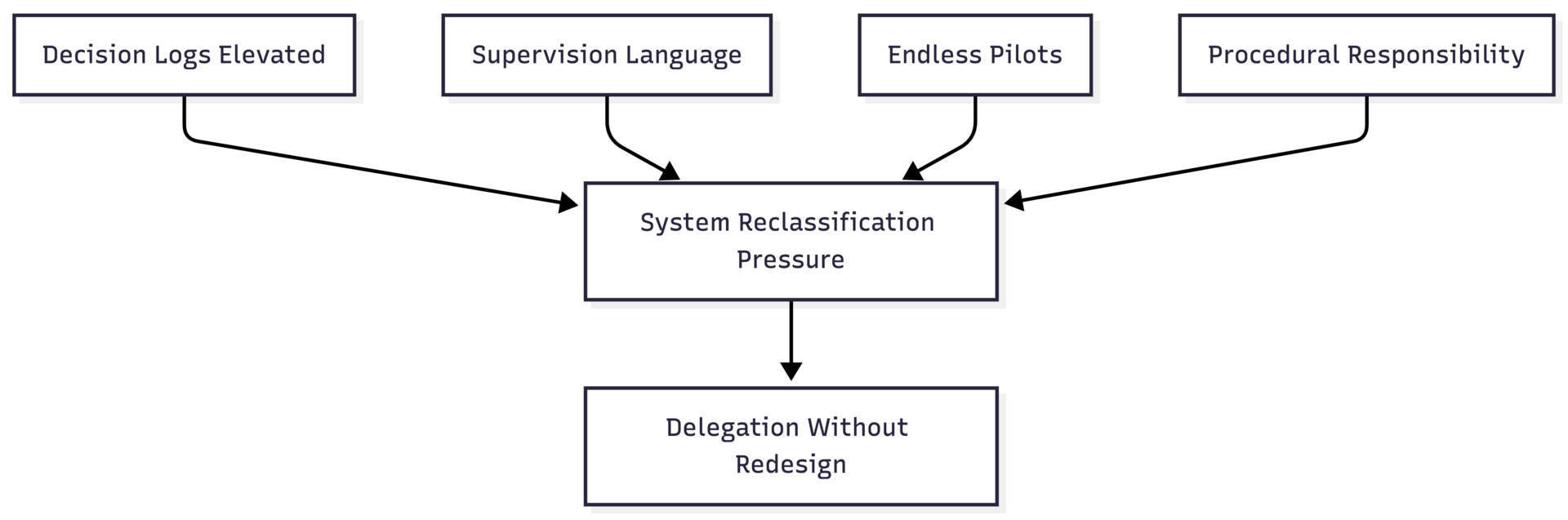

Signal 1: Decision Logs Are Becoming First-Class Artifacts

Across multiple platforms, system designers are elevating decision logs from debug tooling to core infrastructure.

This reflects a quiet recognition: post-hoc explanation is no longer optional when systems act autonomously. Logs are not primarily for transparency. They are for reconstruction after failure.

The signal here is not logging itself, but its promotion into governance discussions.

Figure: Converging signals indicating delegation pressure.

Signal 2: Human-in-the-Loop Is Being Reframed as Supervision

Documentation and vendor language increasingly describe human roles as supervision rather than decision-making.

This linguistic shift matters. Supervision implies acceptance of autonomous action by default, with humans positioned as monitors. This is a delegation posture, even when systems are still marketed as assistive.

Language is often the first place authority moves.

Signal 3: Pilot Systems Are Persisting Indefinitely

Field reports show pilot deployments remaining active for months or years without formal transition into production.

These systems accumulate reliance without accumulating controls. They sit outside formal accountability structures while influencing real outcomes.

This persistence is a governance blind spot, not a technical one.

Signal 4: Responsibility Is Being Assigned Procedurally

In incident responses, responsibility is increasingly framed through process compliance rather than outcome ownership.

Teams demonstrate that procedures were followed, even when no individual or role clearly owned the decision. This is a coping mechanism for ambiguous authority.

Procedural responsibility fills the vacuum left by unclear delegation.

What These Signals Suggest

Taken together, these signals point to the same underlying shift: systems are acquiring decision authority faster than organizations are redesigning responsibility.

This gap is where most applied AI failures incubate.

In the practitioner edition, these research notes include:

Interpretation of signals as system design pressure

Criteria for distinguishing early delegation from normal evolution

Guidance on when signals warrant architectural reclassification

A repeatable delegation checkpoint for applied AI systems

SYNTHESIS

Editorial Close

Issue 2 has examined a single question from multiple angles: when AI systems act, who is actually responsible.

Across implementation briefs, field observations, system comparisons, and research signals, the same pattern recurs. Applied AI systems are being designed and deployed faster than organizations are willing to redraw lines of authority.

The result is not immediate failure. It is ambiguity.

What This Issue Established

Several conclusions now follow clearly:

Systems that behave as delegates cannot be governed as tools

Responsibility does not disappear when authority is transferred

Pilot status does not prevent structural change

Language often shifts before control does

None of these are technical failures. They are classification failures.

The Practical Boundary

The most important decision in applied AI is not model selection or performance tuning. It is the decision to retain authority or to delegate it.

Once delegation occurs, intentionally or otherwise, controls must change. Oversight must become explicit. Intervention must be designed, not assumed. Responsibility must be reassigned before incidents force the issue.

Avoiding this decision does not preserve safety. It defers accountability.

Looking Ahead

Future issues of JAPAI will continue to examine applied AI through this structural lens. Not to catalogue tools, but to surface the design decisions that determine whether systems remain governable at scale.

The aim is not persuasion. It is clarity.

The purpose of The Journal of Applied AI is not to track novelty or celebrate technical feats in isolation.

It exists to surface the structural conditions under which AI becomes durable infrastructure rather than temporary advantage.

That requires uncomfortable clarity: about boundaries, costs, controls, and responsibility.

In the next issue, we will build on these foundations by examining how organizations operationalize oversight once delegation is explicit.

Thank you for reading. This journal is published by Hypermodern AI.