Introduction

Most conversations about artificial intelligence begin and end with models.

Which model is better. Which model is faster. Which model is cheaper. Which model is safer.

This framing is understandable, models are the most visible, novel, and measurable component of modern AI systems. But it is also misleading. In practice, models are rarely the reason AI initiatives succeed or fail.

Applied AI fails, or succeeds at the system level.

Organizations do not deploy models. They deploy systems that contain models, alongside data pipelines, governance constraints, operational controls, and human decision-making structures. When these surrounding systems are weak, no model improvement compensates.

This essay establishes a foundational claim for this journal:

Applied AI is a systems problem before it is a model problem.

The Model-Centric Illusion

In early-stage experimentation, models appear to do most of the work. A prompt produces an output. A demo succeeds. A proof-of-concept convinces stakeholders.

But these early successes occur in environments with:

Manually curated data

Implicit trust

No audit requirements

No cost pressure

No accountability for failure

Production environments remove these assumptions.

What remains is a system that must:

Ingest and validate data continuously

Enforce access and privacy boundaries

Produce outputs that can be audited and explained

Operate under latency and cost constraints

Assign responsibility for outcomes

None of these are model properties.

Anatomy of a Production AI System

Figure: Production AI System Anatomy

This diagram illustrates a critical point: control surfaces sit around the model, not inside it.

Organizations that focus exclusively on model choice leave these surfaces undefined, and failures follow.

Where Systems Fail First

Across implementations, failure tends to cluster in predictable places:

Data boundaries — unclear ownership, poor validation, silent drift

Control gaps — missing audit trails, unenforced policies

Organizational ambiguity — no clear decision rights or accountability

Economic blind spots — costs surface only after scaling

These failures are systemic. Improving the model does not resolve them.

Conclusion

Models matter. But they matter inside systems that determine whether their outputs can be trusted, governed, and sustained.

The purpose of The Journal of Applied AI is to examine these systems, their structures, failure modes, and design constraints; so organizations can move beyond demos and toward durable capability.

This is where applied AI begins.

IMPLEMENTATION BRIEF

Why Most AI Projects Stall After the Demo

The Pattern

The most common failure mode in applied AI is not technical failure.

It is arrested momentum.

A prototype works. A demonstration impresses. A pilot is approved. Then progress slows, ownership fragments, and the initiative quietly dissolves into backlog items and half-maintained notebooks.

This pattern is so common that many organizations now treat it as expected behavior. But it is not accidental, and it is not primarily caused by immature models.

AI projects stall after the demo because the conditions that make demos succeed are incompatible with the conditions required for production systems to operate.

Why Demos Work

Demos succeed because they are built in an environment with:

Hand-curated data

Implicit trust between participants

No enforcement of access controls

No audit or compliance requirements

No latency, reliability, or cost constraints

In other words, demos exist outside the organization’s real operating system.

They answer the question:

“Can this model produce a plausible result?”

They do not answer:

“Can this organization operate this system?”

The Demonstration–Production Gap

The moment an AI initiative moves beyond demonstration, it encounters a different class of requirements.

Figure: Demonstration vs Production Environments

The dashed line is intentional.

Organizations often assume that a working demo naturally evolves into a production system. In reality, the two environments share almost no structural similarity.

Where Momentum Is Lost

Momentum breaks when the project crosses invisible boundaries:

Ownership Boundary

The demo has a champion. Production requires a team.Governance Boundary

Informal trust gives way to formal responsibility.Economic Boundary

Marginal cost becomes visible and recurring.Risk Boundary

Errors now have consequences.

These boundaries are rarely acknowledged explicitly, so they are never designed for.

The Structural Mistake

The mistake is treating the demo as an early version of the system.

It is not.

A demo is a different category of artifact. Its purpose is persuasion, not operation. Attempting to extend it creates friction, rework, and eventual abandonment.

Successful teams do something counterintuitive:

They treat the demo as disposable.

A Better Transition

Instead of asking how to “productionize the demo,” effective organizations ask:

What responsibilities must exist in production?

Where do control, audit, and ownership boundaries belong?

Which parts of the demo can be reused safely, if any?

They design the production system explicitly, even if the model changes.

Closing Observation

AI initiatives stall after the demo not because the demo failed, but because it succeeded in the wrong environment.

Until organizations recognize the demo–production boundary as a structural discontinuity, they will continue to confuse proof with readiness, and momentum will continue to evaporate.

IMPLEMENTATION BRIEF

The Cost of Treating Models as the Product

The Mistaken Abstraction

Many AI initiatives are framed, implicitly or explicitly, as efforts to "deploy a model."

This framing is subtle, but consequential.

When the model is treated as the product, everything else becomes secondary: data quality, control surfaces, governance, integration, and operational cost are deferred or ignored. Early progress appears rapid. Long-term fragility is guaranteed.

The result is a system that looks sophisticated on paper but behaves unpredictably in practice.

Why the Abstraction Persists

Treating the model as the product persists for three reasons:

Models are tangible — they can be named, benchmarked, and compared.

Vendors reinforce the narrative — products are sold as model upgrades.

Early success masks structural gaps — demos rarely surface system costs.

None of these reasons survive contact with production.

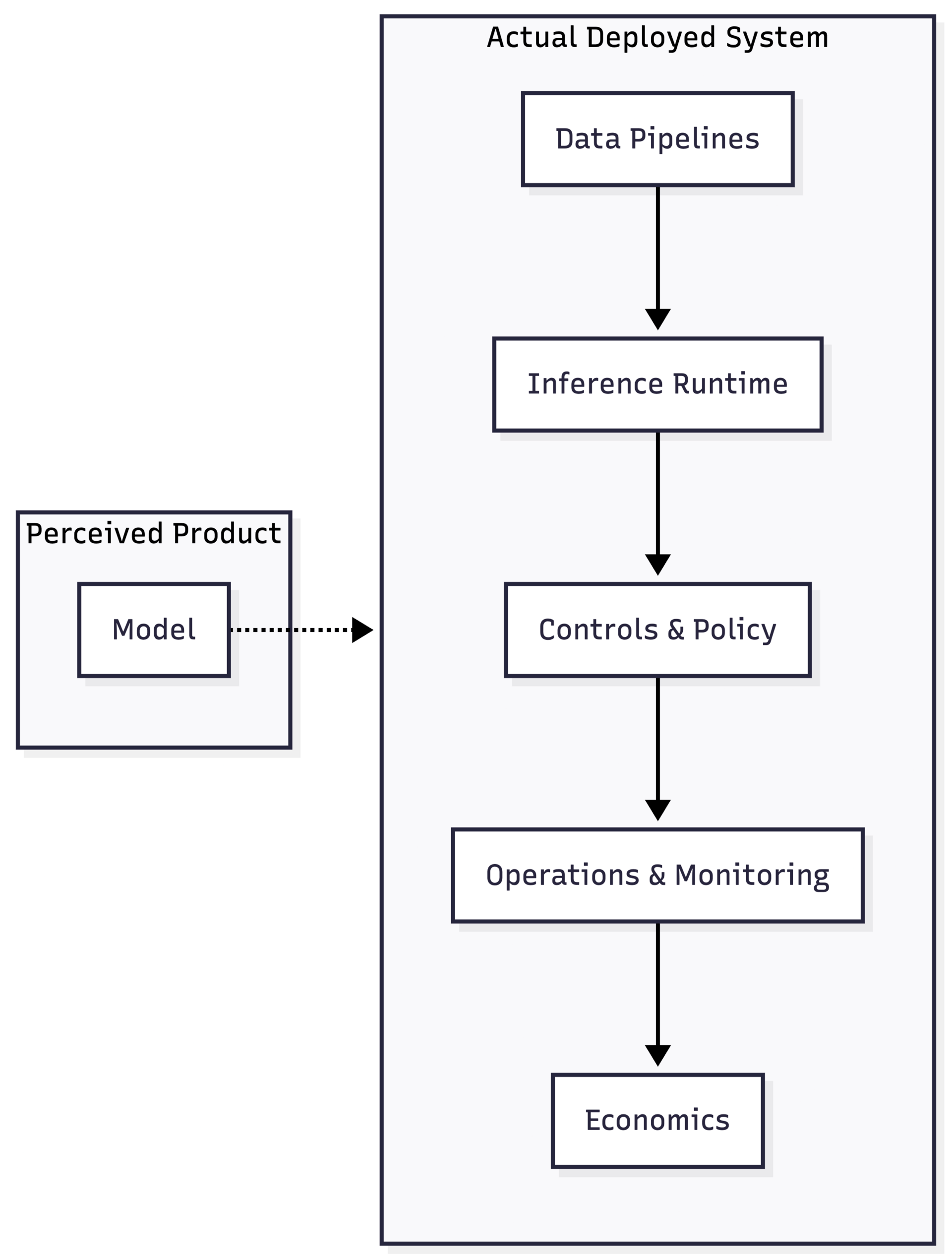

What Actually Gets Deployed

Organizations never deploy a model in isolation. They deploy an operating system around a model.

Figure: Perceived Product vs Actual Deployed System

The dashed line reflects the mismatch between perception and reality. The model is only one dependency among many, and rarely the dominant one.

Hidden Costs Emerge Over Time

Once a system is in use, costs surface that were not modeled:

Inference cost grows non-linearly with adoption

Latency constraints force architectural compromise

Monitoring and audit become mandatory

Failure handling requires human escalation

These costs do not belong to the model. They belong to the system.

Organizational Consequences

When the model is treated as the product:

Ownership defaults to technical teams

Business accountability becomes ambiguous

Governance is perceived as friction

Failures are blamed on "model quality"

This dynamic delays corrective action and entrenches fragility.

A More Durable Framing

Durable AI initiatives reverse the abstraction:

The system is the product

The model is a replaceable component

Value is measured at the outcome boundary

Under this framing, model upgrades are routine changes, not existential events.

Closing Observation

Treating models as the product simplifies early storytelling at the expense of long-term stability.

Organizations that want AI to endure must design, own, and govern systems — not chase models.

FIELD NOTES

What Teams Discover After the First Pilot

Context

These field notes synthesize recurring observations from organizations after their first AI pilot moves beyond experimentation and encounters real operating conditions.

They are not case studies. They are patterns.

Observation 1: Data Ownership Was Never Agreed

Teams often discover, too late, that the data powering the pilot does not have a clear owner.

During the pilot:

Data was copied manually

Access was granted informally

Quality issues were corrected ad hoc

After the pilot:

Source teams resist ongoing responsibility

Legal and compliance surface new constraints

Changes to upstream systems break assumptions

What appeared to be a technical dependency reveals itself as an organizational one.

Observation 2: Governance Appears Suddenly, Not Gradually

Governance is often absent during pilots and overwhelming immediately afterward.

There is rarely a smooth transition.

Figure: Governance is a Production Blocker

Teams expect governance to scale incrementally. In practice, it arrives as a gate.

Observation 3: Reliability Becomes the First Complaint

Users tolerate errors in pilots.

They do not tolerate inconsistency in daily workflows.

Once the system is used regularly:

Latency is noticed

Output variability becomes disruptive

Failure recovery is expected, not optional

The system is no longer judged by capability, but by predictability.

Observation 4: Accountability Is Ambiguous

After the pilot, a new question emerges:

Who is responsible when the system is wrong?

Common answers include:

The data team

The model provider

The product owner

“The business”

None of these are sufficient.

Observation 5: Costs Become Visible Only After Adoption

Inference costs, monitoring overhead, and support load often appear only once usage grows.

By then:

Budget ownership is unclear

Cost controls are absent

Retrenchment becomes political

Economic reality arrives late, and loudly.

A Structural Summary

These observations are symptoms of the same condition: the pilot was never treated as a boundary-crossing event.

Figure: Experimentation Operations ≠ Production Operations

The dashed transition is where most initiatives falter.

Closing Note

Teams do not fail because they ignore these realities.

They fail because the system does not surface them early enough.

Making these constraints visible, architecturally and organizationally, is the difference between a pilot and a capability.

VISUALIZATION

Pilot vs Production: The System Gap

Framing

AI pilots and AI production systems are often discussed as points along a continuum.

Structurally, they are not.

What follows is a direct system comparison. The diagrams are the argument.

Pilot System

A pilot is optimized for speed, persuasion, and learning under uncertainty.

Figure: Pilot System Flow

Characteristics

Data is curated, not governed

Trust is interpersonal

Failures are tolerated

Costs are invisible

Responsibility is implicit

The system works because the environment is forgiving.

Production System

A production system is optimized for reliability, accountability, and repeatability.

Figure: Production System Flow

Characteristics

Data has owners and contracts

Trust is encoded in controls

Failures must be handled

Costs are continuous

Responsibility is explicit

The system works because the environment is constrained.

What Changes — And What Does Not

The model may remain the same.

Almost everything else changes.

Figure: Pilot to Production Flow

The boundary crossing is not technical. It is organizational and economic.

Structural Conclusion

Pilots succeed by avoiding constraints.

Production systems exist because constraints are enforced.

Treating one as an early version of the other creates fragility, delay, and stalled initiatives.

The correct question is not:

“How do we productionize this pilot?”

It is:

“What system must exist for this capability to operate responsibly?”

RESEARCH & SIGNALS

Purpose

Research & Signals tracks developments that materially affect how AI systems are built, governed, and operated — not headlines, launches, or hype.

Each signal is interpreted for structural consequence.

Signal 1: Models Are Getting Cheaper & Faster Than Systems

Observation

Model inference costs continue to fall, while total system cost does not.

Why It Matters

This widens the gap between perceived affordability and actual operational expense. Organizations underestimate cost because they benchmark models, not systems.

Structural Implication

Cost governance must move upstream into architecture and usage design, not model selection.

Signal 2: Enterprise Buyers Are Asking for Control, Not Capability

Observation

Procurement and risk teams increasingly prioritize data locality, auditability, and override mechanisms.

Why It Matters

Capability without control is now viewed as liability.

Structural Implication

Vendors that cannot expose governance surfaces will stall in enterprise adoption regardless of model quality.

Signal 3: “Agent” Framing Is Outpacing Operational Reality

Observation

Agent-based systems are widely discussed, but rarely deployed beyond constrained environments.

Why It Matters

The abstraction leap obscures responsibility, failure handling, and cost propagation.

Structural Implication

Expect a correction toward bounded, inspectable workflows rather than autonomous general agents.

Signal 4: Internal AI Platforms Are Reappearing

Observation

Organizations that previously resisted internal platforms are revisiting them to regain consistency and control.

Why It Matters

Decentralized experimentation creates governance debt.

Structural Implication

Platform thinking is returning — not for speed, but for survivability.

Signal 5: Evaluation Is Shifting From Accuracy to Impact

Observation

Teams are moving away from single-metric evaluation toward outcome, risk, and cost measures.

Why It Matters

This reframes success at the system boundary rather than the model boundary.

Structural Implication

Evaluation tooling will increasingly sit alongside monitoring and audit, not experimentation.

Closing Note

These signals point in the same direction: AI is entering a phase where structural soundness matters more than novelty.

Organizations that adapt their mental models accordingly will compound advantage. Those that do not will continue to chase capability without durability.

SYNTHESIS

Capability Is Not the Same as Readiness

This issue has examined a single, recurring failure pattern in applied AI: confusing demonstrated capability with organizational readiness.

Across essays, briefs, diagrams, and field notes, the same boundary appears repeatedly.

Capability answers the question:

Can this work?

Readiness answers a different one:

Can we operate this responsibly, repeatedly, and at scale?

Most AI initiatives falter not because the answer to the first question is no, but because the second is never fully asked.

Demos succeed by removing constraints. Production systems exist because constraints are enforced.

Between the two sits a discontinuity that cannot be bridged by iteration alone. It requires explicit system design, ownership, governance, and economic clarity.

When these are absent, progress slows, responsibility fragments, and promising capabilities quietly stall.

The purpose of The Journal of Applied AI is not to track novelty or celebrate technical feats in isolation.

It exists to surface the structural conditions under which AI becomes durable infrastructure rather than temporary advantage.

That requires uncomfortable clarity: about boundaries, costs, controls, and responsibility.

Future issues will introduce higher-resolution diagrams and deeper structural analysis for practitioners building these systems.

In the next issue, we will examine a different boundary: the difference between automation and delegation, and why collapsing the two creates risk that organizations are only beginning to recognize.

Thank you for reading. This journal is published by Hypermodern AI.